Amisfield Prisoner of War Camp 16A

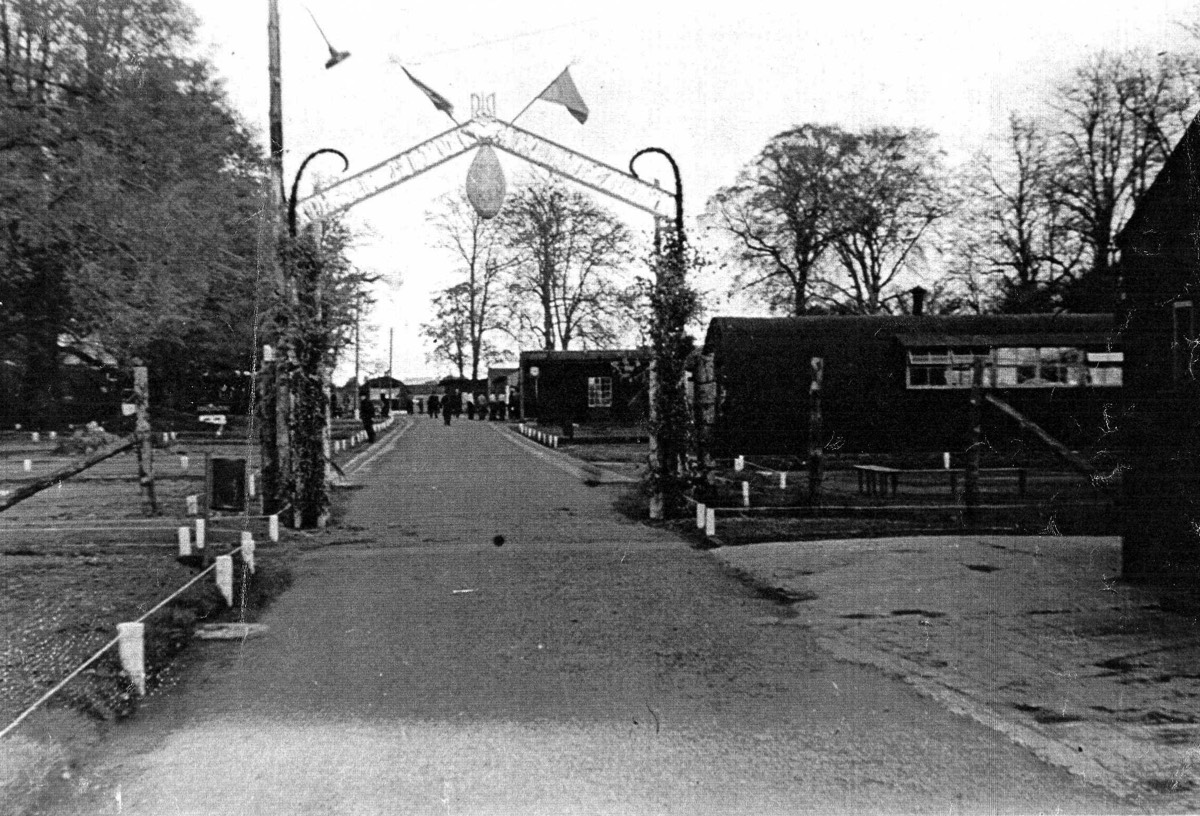

Amisfield PoW camp 16A [243] about 1947.

The road still exists and runs directly to Haddington Golf Course Clubhouse.

Amisfield Camp before the PoWs

“I had quite a bit to do with the military occupation of the area during the war. I was the official Chaplain to the C. of E. troops and as Amisfield Camp was occupied by British troops [for a long time], I had a lot of contact with them. I think the first lot to come were the Sherwood Foresters - shortly after Dunkirk [perhaps June/July 1940] - and they were a pretty dis-spirited lot considering what they had come through. We then had a long occupation by the Polish Army and they [made] quite an impression on the town and district - especially [on] the ladies! I well remember the scenes when they finally marched away and the street was lined with weeping women!! They left a considerable legacy behind them...

Then, in preparation for D Day we had a contingent of the R.E.M.E. and R.A.S.C. stationed in the camp getting vehicles ready. They were a good bunch and I made several lasting friendships. Our rectory was regarded as ‘Open House’ and the one thing they missed most was a hot bath. So, any man who wanted to came - provided he brought his own soap and towel - and my wife always gave them coffee afterwards. ...Trinity Hall was given over as a Church of Scotland canteen and my wife was much involved in that, being second in command to the Parish Minister’s wife who ruled the place with a rod of iron!”

Amisfield PoW camp 16A, Haddington

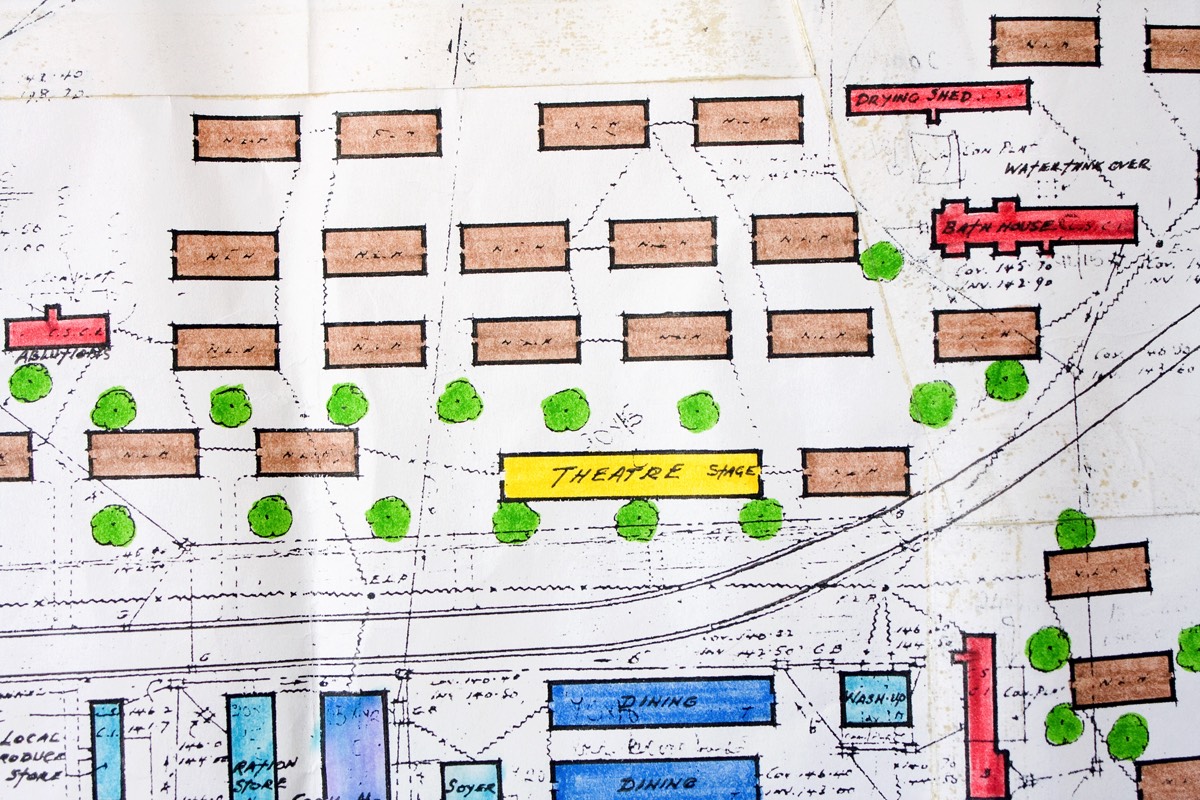

A plan of Amisfield PoW camp 16A

[courtesy of Haddington Golf Club]

Detail from the map above showing the position of the theatre, dining huts and (in brown) some of the accommodation blocks.

Eyewitness - Harry Dittrich

Harry Dittrich had arrived in Gosford in 1944. Harry wrote:

“After a few weeks [at Gosford PoW camp] all the ‘foreigners’ were assembled and transported to PoW camp No 16A in Haddington, all eight hundred of us. I spent two years there. We had to work on farms but it was a nice camp, very tidy and run by ourselves. We had a theatre and a good band, plays were written and concerts laid on frequently. Many of the Austrians came from Vienna. Music and song were in their blood and what they had to offer was really outstanding. I had a lot of friends among them.

During those two years I had the first opportunities of closer contact with the local population and getting a picture of life in Scotland. I was very impressed by what I saw. It was such a peaceful and friendly land, entirely different from what I had known on the continent. Of course, I had difficulty with the language at first but I soon started to pick up a few words here and there. After two years in Haddington the camp was closed. We were sent back to the main camp in Gosford.”

Inspection by the International Red Cross - life in Amisfield

Just prior to the inspection some 200 Austrians had been transferred to other camps and replaced by others from Gosford. In political terms the PoWs were described in the nomenclature of the time as ‘Nearly White‘. This meant that they were not seen as particularly indoctrinated by Nazi ideology. Two other categories existed, ‘Grey’ and ‘Black‘ and the latter was usually reserved for the SS. No complaints were made about the food which is not surprising as PoWs were supposed to be fed to the same standard as British soldiers and they were fed better than civilians.

The menu on the day of inspection was as follows:

Breakfast: bread, marmalade and tea;

Dinner: bread, sausage , margarine and tea;

Supper: a small sausage, porridge, vegetables, potatoes and tea .

The health of the prisoners was described as ‘Good‘ but fifty per cent of the PoWs wore very dilapidated uniforms. 405 were actually out of the camp working on farms, saw-mills, etc.. Some of the PoWs were being billeted in the surrounding area, if their work took them too far away from Amisfield for daily transport to be a realistic option.

A view of the chapel built by the prisoners at Amisfield inside a Nissen hut

A football pitch was available and a library of around 300 books helped PoWs while away the hours in either amusement or education. There was a good following for English classes (some 181 attended), while others attended German class (sixty-five), French class (31), mathematics (31) and a stenography class (33). The director of studies was Gefreiter Karl Stochl.

Music, as Harry Dittrich confirmed above, played a significant role in the camp’s life. An orchestra of eight members had quite a collection of instruments to play. It included: a piano, cello, double-bass, trumpet, two violins, two saxophones, a clarinet, banjo, guitar, drum, accordion and zither. Fifteen PoWs provided a theatre group but the camp didn’t have a choir at this time. Films were a regular amusement with newsreels predominating but also showing cultural films and ‘ ...one German film’. Interestingly, the mail, something PoWs understandably yearn for, was coming and going quite successfully and the ICR report stressed that ‘Correspondence with the Russian zone was permitted’.

All in all the Inspector found Amisfield to be “A very good camp” and the only request from the Camp Leader was for more books.

This model of a British aeroplane was made by a PoW in Amisfield. It may represent an Avro Anson and was one means prisoners had to wile away their hours in captivity. Such models were often sold as a means of getting hold of hard cash or they might be given to local children around Christmas time.

[Model owned by D. Scott, Haddington]

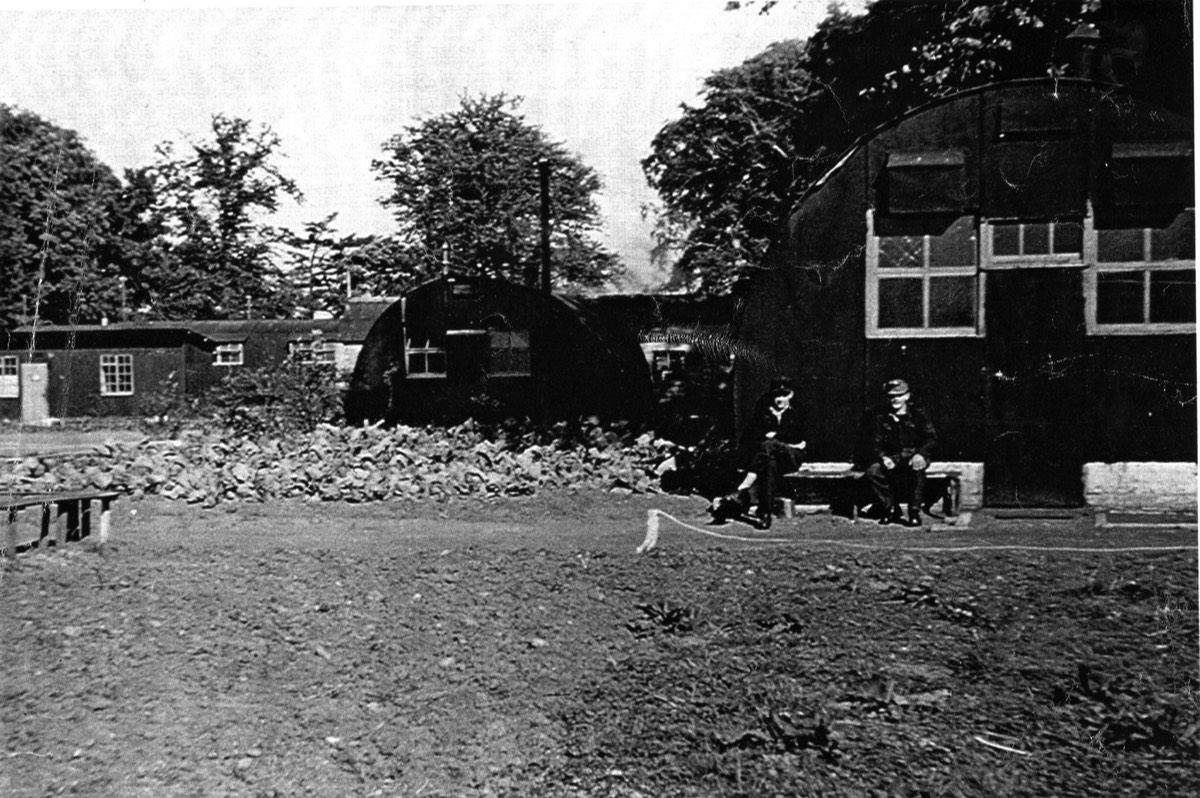

A sunny day in Amisfield: two prisoners can be seen sitting by their vegetable patch outside their Nissen hut accommodation.

PoWs worked on East Lothian farms

David Scott, son of Tom Scott, the farmer at Howden, remembers that German PoWs were normally given tea and scones during their work breaks but he also remembered that this didn’t always apply. On one occasion the Camp CO at Amisfield phoned David’s father to say that the group of PoWs due to work on the farm that day were not to be given any such ‘luxuries’. Unusually, when these four men arrived they were escorted by an armed soldier and were marched, parade-ground fashion, from the lorry to the farm and put to work. These men, apparently, were still regarded as convinced Nazis sure that Hitler would still win the war. In 1947 Guenter Ruust, a former PoW in Amisfield camp, wrote from No 63 PoW camp, Balhary Estate, Alyth, Perthshire, to Tom at Howden farm. He had clearly been well treated at Howden and was finding life tough and lonely during the severe winter of 1947. He wrote:

'29th January 1947

Dear Tom, Many greetings to you and your whole family from Guenter. You will ask who is writing such words to me. Well if you will remember yourself back to the autumn of 1945 you will still know six lads who were working on your farm at that time. One of them is I. I am alone here. Where the others are I don't know. I do the same job on farms here as I did on yours. How are your family? I hope everything will be alright. I do often remember your kindness to us. So we are still obliged to us [sic] in many things....Will you please tell Alex my best wishes and greetings. I am sorry for missing his address. He may write to me if he like. Will in expecting an answer from you.

With kindest regards,

Your Guenther"

Guenter, whose command of English was still growing, wrote again on the 15th March 1947, possibly in thanks for some cash Tom Scott had sent him. Life was hard for Guenter in the severe weather conditions. He wrote:

'29th Marz 1947

Dear Tom, After a long time now I am able to thank you very much for your lines and that enclose. It is because we don't get so much postage letters. I have been glad to hear that you re still alright and doing well. Your enclose came just in time because we are out of work already over five weeks. We are all snow bound. It is a very bad time for us as we have no pay, there fore we cannot buy things wich we want and food supply is bad too. We are all wishing that this winter shall soon be off. It is making trouble for all of us. Some squads are casting snow ten and more feet high. Your little son David, I''m wishing my best luck for being well in future. Besides some about Alex. It seems to me he has not got my letter wich I wrote to him about four weeks ago. Did you meet him some day? I hope it isn't something wrong with him. Would you mind giving me a reply? I hope you understand my bad English in spelling and writing. All my best wishes to you and your father's family.

With kindest regards, your Guenther."

[Thanks to David Scott for permission to use these two letters]

The farmer, Mr Dingwall, of Dovecot Market Gardens, Haddington, with two unidentified girls (possibly Land Girls) and two PoWs.

After the war

Disaster in a minefield

A Prisoner of War reunion

Gunter Schumacher, Prisoner of War

His experiences in Amisfield were much better than those he’d undergone in a camp in Belgium and like many others, he felt freer and happier. As he said, “You have to live life as it is.” Like many of his fellow prisoners, he had been sent to work on farms in the nearby countryside. Satisfying his curiosity was an additional reason for returning, since he’d never been able to see it while he was a prisoner.

When he arrived at the camp in 1998, Gunter was surprised to meet another former Amisfield PoW, Rudi Franzel. Like Gunter, Rudi had married and remained in the UK after the war and both men were soon able to swap stories of their shared experience.

Two former PoWs at Amisfield PoW camp meet after fifty-two years

Rudi Franzel and Gunter Schumacher in front of Amisfield Park gates

Rudi (centre) and Gunter (right) being interviewed by David Haire on the site of Amisfield PoW camp in September 1998

Amisfield camp after the war: the Ukrainians

The Ukrainians, however, weren’t unhappy. They’d been ‘civilianised’ in the parlance of the day and were merely awaiting the day when they could leave and re-enter society in whichever country that might be. They had been given civilian clothing and were willing to pay £1 10 shillings [£1 50p] for their weekly accommodation and food. The kitchens were described as good and the Ukrainians were ‘...satisfied...’ with the food. The minimum wage was £4. 10sh [£4 50 pence] and was often earned in the fields on the farms. All were covered by the new National Health Insurance scheme and it was proposed by the Ukrainian Welfare Committee which ran the internal affairs of the camp, that English lessons would begin in the winter months. The men were eager for the services of a Greek Orthodox priest but were free to attend local churches.

Ukrainians preparing food with local kitchen staff, Amisfield camp

Ukrainian former PoWs at Amisfield camp, post-war

Amisfield Ukrainian choir

Ukrainians and some of the local kitchen staff, Amisfield camp